This portrait series connects viewers with real people living through conflict around the world — the human stories behind the headlines. Each drawing is shaped by first-hand testimony, capturing experiences of war, displacement, resilience, and survival that rarely receive the attention they deserve.

Drawing invites us to slow down, to witness with empathy instead of horror, to cherish human connection and reimagine the world's most urgent stories.

These ten testimonies are part of a growing body of work dedicated to preserving testimony from individuals affected by conflict, displacement, and climate crisis.

1. Unknown man, double amputee, Kabul, Afghanistan, 2014

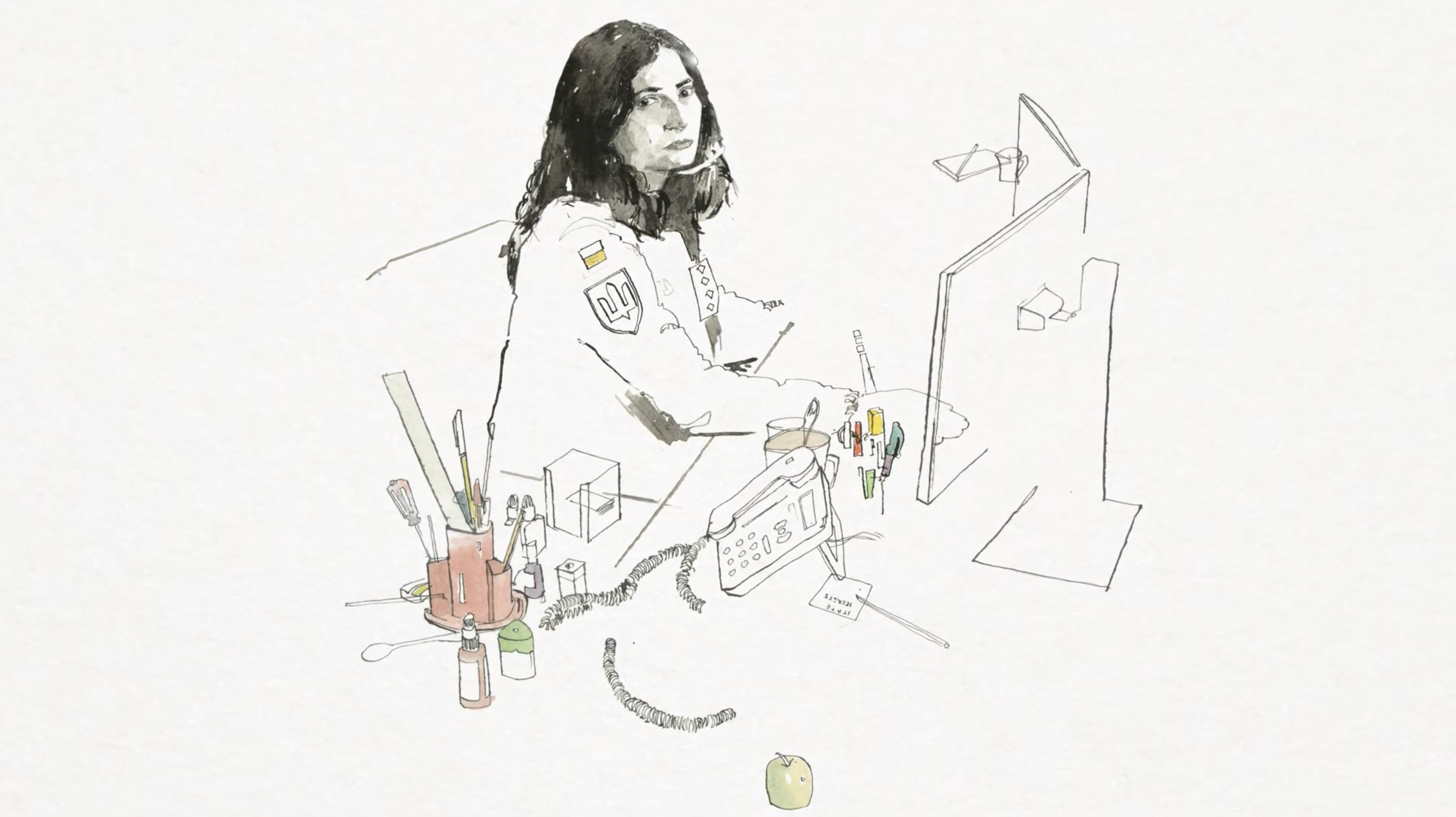

2. Liza, 26 — Kyiv, Ukraine, 2023

Liza is a captain with Ukraine’s State Space Agency, responsible for capturing satellite imagery across eastern Ukraine to monitor tank movements and radio activity for military analysis. Her career path is very different from her friends who are designers, musicians and DJs. She is one of few young women working in a predominantly older, male environment.

When colleagues relocated to Lviv, she chose to remain in Kyiv with her twin brother. Born in Moscow, she moved to Ukraine at age three. Her father died of an overdose when she was two, and her mother now lives in Wales. She no longer maintains contact with extended family in Russia due to political divisions.

Although she is not physically on the frontline with a gun in her hand, she understands how important her work is to the wider war and her colleagues fighting on the ground. It spurs her to work harder to protect them. I was inspired by her bravery running her life alongside war as so many did.

As a closeted gay woman in the military, she navigates significant professional constraints. While not illegal, disclosure would most likely limit promotion opportunities. Although she did proudly tell me to publish those details because she didn’t expect to stay long in the military.

3. Mustafa al Taee - Hamam al Alil, Iraq, 2017

“Just ask for Mustafa al-Taee” is the advice from the local store keeper. Which we do and we are directed straight to his house in Hamam al Alil. Mustafa is a locally famous artist. Throughout the ISIS occupation of Hamam al Alil he drew the atrocities that he witnessed being carried out on the local people and soldiers. He describes how he finds drawing therapeutic and how he can’t stop doing it. Piled in the corner are tens of these drawings; people with their heads cut off, soldiers hung upside down on barbed wire.

When ISIS discovered Mustafa was drawing, a practice that is ‘haram’ or forbidden he was beaten. He was told he could never do it again. But now he exhibits his work in the town as a reminder of the horrific occupation.

4. Mama Nazak, 62 - Syria/Turkish border, 2012

Mama Nazak was a geography teacher at the university in Damascus. Having been hung by her hands for 20 days by the Hafez al Assad regime for not supporting the Baath party, she left Syria in 1980, only to return six years ago.

Mama Nazak had three sons. Her son Fras was killed fighting for the Free Syrian Army against the regime. Juan was shot in the lower arm whilst trying to save Fras and remains disabled. And Judi on a separate occasion was shot in the back, leaving him paralyzed from the waist down.

She described what had happened to them like this: “You can say I had three flowers in my garden, one was eaten by the beast and two trampled down with the beast’s foot and walked away.”

5. Khalid, 11 - Syria/Turkish border, 2012

Khalid’s story is hard to witness, but it is one of hope. I met Khalid in the same refugee camp where I met and drew Mama Nazak. Khalid was 11 when his father was shot at home by the government militia with a heavy machine gun.

Him and his mother managed to escape to the Turkish border. But on the way they were stopped by a military check point. His mother, realising what was happening, dropped Khalid from the car and told him to run. He did, but he turned around to see his mother dragged from the car and decapitated.

Wrapped in his Syrian revolutionary flag he sat with us and recounted this story from only 20 days earlier. I don’t think I have ever met a braver person. He went on to say “I want to be a doctor to heal the injured people of the war and if somebody enters our house again, I want to protect my family. I want to protect others if somebody wants to enter their house.”

Khalid had been adopted in the refugee camp by Mama Nazak. They had found each other in the worst circumstances imaginable - but at the very least they were not alone.

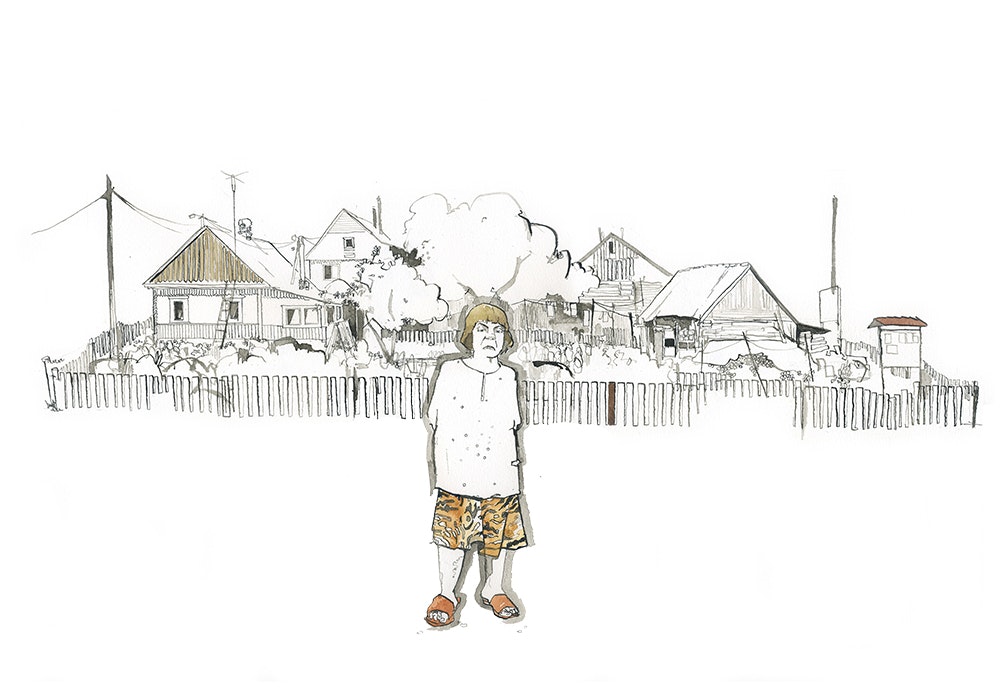

6. Tamara, for Amnesty International, as part of a campaign to outlaw the death penalty in Belarus, 2017

Tamara lives outside Minsk in Belarus, she is a university educated mother of two. Her son Pavel was executed on death row in 2012. Under Lucashenko Belarus is the last country in Europe to still practise capital punishment.

She talked fondly about how as a young woman she was a sprinter, then an ice skater – and to prove it she got down on the floor of her kitchen and did the splits. Now ruined by the loss of her son and stigmatised by society for his crime she is forced to retreat into her small home.

Tamara received her last letter from her son Pavel on 16 April 2012 asking her to send more books. Months later she received a note from his lawyer saying “ [he] left the prison with his personal belongings in accordance with his sentence” His body would not be handed over.. She was never allowed a funeral, the death was never confirmed and she doesn’t know where his body is buried.

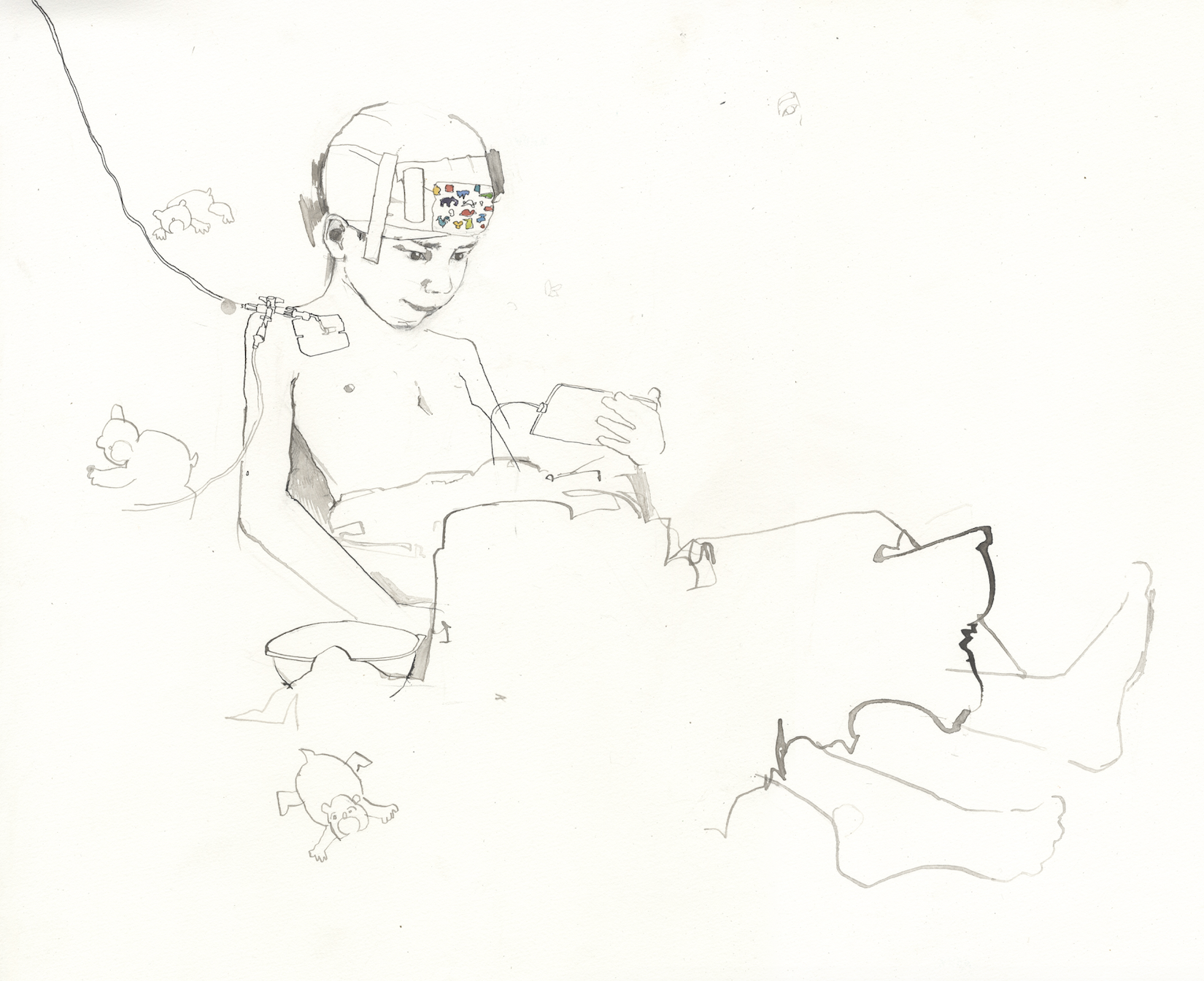

7. Volodymyr, 7 - Kharkiv, Ukraine, 2022

On the fourth floor of Kharkiv City Clinical Hospital, Volodymyr lay recovering from two operations after being shot at a checkpoint — a bullet lodged in his brain, his mother killed beside him. In a cramped two-bed room, he shared space with his father, Stanislav, and three-year-old brother, Viktor, as the family attempted to rebuild life around an absence that defined everything.

A month after the attack, Volodymyr was relearning how to use his legs. Muscle loss had shrunk his body against the bandaged bulk of his head, bright animal plasters softening the starkness of his injuries. Away from the boys, Stanislav recounted the day his wife, Daria, died. After nearby rocket strikes shattered their apartment windows, the family fled by car. Within minutes, their vehicle was fired upon. Daria, 34, was killed instantly; Volodymyr was critically wounded.

Stanislav scrolled through photographs — beach trips, wedding-day traditions, family milestones — until they stopped at an image of the bullet-ridden car. He disputes official claims that the incident was accidental, insisting no warning was given.

Doctors monitored Volodymyr’s swelling brain, uncertain if more surgery would follow. Still, small movements offered hope. Before the war he showed talent in robotics and engineering; his father clung to that future.

A year later, the boys lived with grandparents. Volodymyr walked again, playing with toy tanks. Viktor bounded across the room. Grief remained but family life continued - albeit never the same again.

8. Hasnaa - East Ghouta, Syria, 2024

Hasnaa, Teacher, activist Eastern Ghouta, Damascus

In 2011 Hasnaa was pregnant with twins, living in Eastern Ghouta, a Sunni area of Damascus. By the time she was full-term, her husband, a Palestinian Syrian who worked for the state, left her, accusing her of being a “terrorist” because the students she taught came from Sunni families. Not long after giving birth, she began joining protests against the regime. In 2015 she was arrested. She was transferred from one security branch to another—five in all—the most notorious of them being al-Khatib, where she was beaten and forced to watch others being tortured. She shared a two-by-two-meter cell with fourteen other women.

When she returned home, she lived under siege for three years. Finally driven from her home by the government’s bombing campaign, Hasnaa moved her family to a nearby shelter in Harjalleh.

We spent the last two months of 2018 living underground, she told me. My children didn’t know what a banana was, or an orange, or chocolate.

Eventually she escaped to Azaz in northern Syria where she worked to establish a network of several dozen female journalists reporting only on women’s issues in Syria, known as the Akhbarna Network (“Our News Network”).

Syrian women should not accept leadership, social, or political positions that are less than what they truly deserve, she told me. Women must support each other by forming alliances, groups, or unions through which they can advocate for their rights and stand up for oppressed women’s causes.

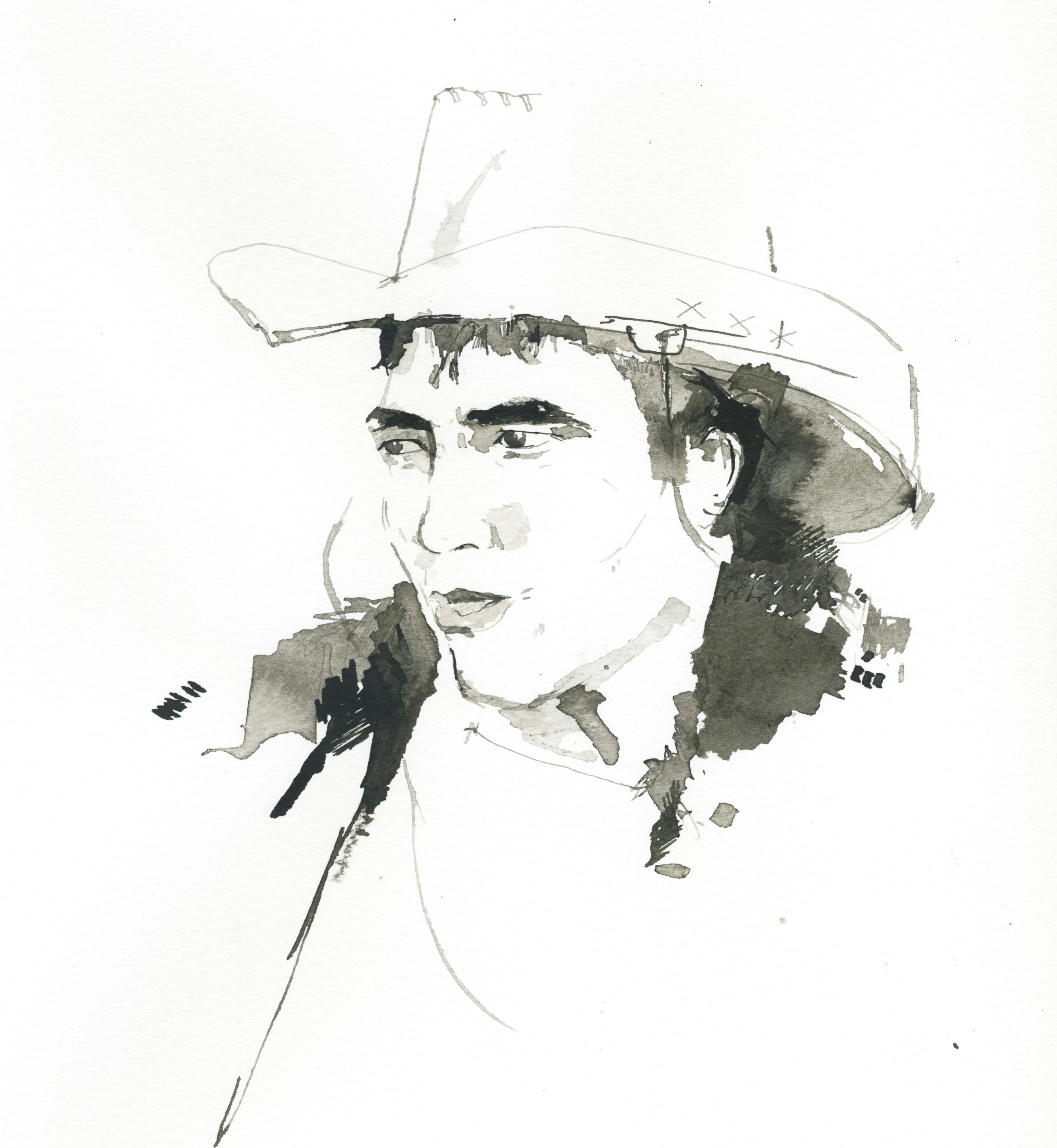

9. Abdullo, Dushanbe, Tajikistan, 2017

Abdullo is a young man from the Rasht valley in Northern Tajikistan. Tajikistan is one of the poorest countries on earth - the economy relies on remittances from Russia.

I followed Abdullo from his rural home, leaving behind his family and making the four day train ride to Moscow, via Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. There he worked as an informal labourer, living in the flats he was decorating and sending money back to his family. It was short lived, like many others he was deported and returned home soon after.

These drawings were made for a New York Times Opdoc film called “2300 Miles to Work” directed by Tim Brown @tabrown and produced by @joeschottenfield

10. Mohammad - West Bank, 2016 for Oxfam

Mohammed, a Palestinian Bedouin boy, is 10 and stands under a tree with an old gas mask on his head. He found it near his home in E1, Area C. It is something people in the community wear when tear gas is fired at them by the Israeli forces. Today he uses it as a toy.

Israeli Defence Force policies and practices in the West Bank have long violated basic rights and undermined the presence and development of Palestinian communities, often resulting in forced displacement and increased dependency on humanitarian assistance.

Some drawings become less relevant over time, we had naively hoped at the time that the lives of 10 year olds in Palestine and Gaza would improve, but the reality - another 10 years on couldn’t be further from the truth.